1. When you are eighty years old, and in a quiet moment of reflection narrating for only yourself the most personal version of your life story, the telling that will be most compact and meaningful will be the series of choices you have made. In the end, we are our choices.

2. Relentless and ruthless. Those words show up repeatedly in the following pages. They are extreme but familiar values at most successful companies. Getting the lethal combination precisely right has been Bezos’s prodigious talent and perhaps Amazon’s greatest asset.

3. There is so much stuff that has yet to be invented. There’s so much new that’s going to happen.

4. Amazon’s internal customs are deeply idiosyncratic.

5. “If you want to get to the truth about what makes us different, it’s this,” Bezos says, “We are genuinely customer-centric, we are genuinely long-term oriented and we genuinely like to invent. Most companies are not those things. They are focused on the competitor, rather than the customer. They want to work on things that will pay dividends in two or three years, and if they don’t work in two or three years they will move on to something else. And they prefer to be close-followers rather than inventors, because it’s safer. So if you want to capture the truth about Amazon, that is why we are different. Very few companies have all of those three elements.”

6. I brought him very bad news about our business, and for some reason, he got excited.

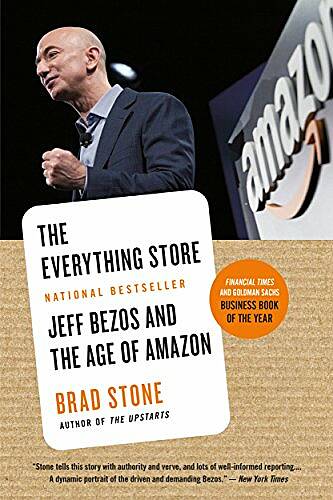

7. The goal of this book is to tell the story behind one of the greatest entrepreneurial successes since Sam Walton flew his two-seat turboprop across the American South to scope out prospective Walmart store sites. It’s the tale of how one gifted child grew into an extraordinarily driven and versatile CEO and how he, his family, and his colleagues bet heavily on a revolutionary network called the Internet, and on the grandiose vision of a single store that sells everything.

8. Amazon.com was an idea floating through the New York City offices of one of the most unusual firms on Wall Street: D. E. Shaw & Co. A quantitative hedge fund, DESCO, as its employees affectionately called it, was started in 1988 by David E. Shaw, a former Columbia University computer science professor. Along with the founders of other groundbreaking quant houses of that era, like Renaissance Technologies and Tudor Investment Corporation, Shaw pioneered the use of computers and sophisticated mathematical formulas to exploit anomalous patterns in global financial markets.

9. The broader financial community knew very little about D. E. Shaw, and its polymath founder wanted to keep it that way.

10. Shaw felt strongly that if DESCO was going to be a firm that pioneered new approaches to investing, the only way to maintain its lead was to keep its insights secret and avoid teaching competitors how to think about these new computer-guided frontiers.

11. Bezos was in his midtwenties at the time, five foot eight inches tall, already balding and with the pasty, rumpled appearance of a committed workaholic. He had spent five years on Wall Street and impressed seemingly everyone he encountered with his keen intellect and boundless determination.

12. Minor remembers that Bezos had closely studied several wealthy businessmen and that he particularly admired a man named Frank Meeks, a Virginia entrepreneur who had made a fortune owning Domino’s Pizza franchises.

13. Bezos also revered pioneering computer scientist Alan Kay and often quoted his observation that “point of view is worth 80 IQ points”—a reminder that looking at things in new ways can enhance one’s understanding.

14. He went to school on everybody. I don’t think there was anybody Jeff knew that he didn’t walk away from with whatever lessons he could.

15. Bezos would later say he found a kind of workplace soul mate in David Shaw—“one of the few people I know who has a fully developed left brain and a fully developed right brain.”

16. At DESCO, Bezos displayed many of the idiosyncratic qualities his employees would later observe at Amazon. He was disciplined and precise, constantly recording ideas in a notebook he carried with him, as if they might float out of his mind if he didn’t jot them down. He quickly abandoned old notions and embraced new ones when better options presented themselves.

17. He was “the most introspective guy I ever met. He was very methodical about everything in his life.”

18. So in 1994, when the opportunity of the Internet began to reveal itself to the few people watching closely, Shaw felt that his company was uniquely positioned to exploit it. And the person he anointed to spearhead the effort was Jeff Bezos.

19. Shaw and Bezos discussed another idea as well. They called it “the everything store.”

20. Bezos interpolated from this that Web activity overall had gone up that year by a factor of roughly 2,300—a 230,000 percent increase. “Things just don’t grow that fast,” Bezos later said. “It’s highly unusual, and that started me thinking, What kind of business plan might make sense in the context of that growth?”

21. What happened next became one of the founding legends of the Internet. That spring, Bezos spoke to David Shaw and told him he planned to leave the company to create an online bookstore. Shaw suggested they take a walk. They wandered in Central Park for two hours, discussing the venture and the entrepreneurial drive. Shaw said he understood Bezos’s impulse and sympathized with it—he had done the same thing when he’d left Morgan Stanley. He also noted that D. E. Shaw was growing quickly and that Bezos already had a great job. He told Bezos that the firm might end up competing with his new venture. The two agreed that Bezos would spend a few days thinking about it.

22. Bezos would later describe his thinking process in unusually geeky terms. He says he came up with what he called a “regret-minimization framework” to decide the next step to take at this juncture of his career. “When you are in the thick of things, you can get confused by small stuff,” Bezos said a few years later. “I knew when I was eighty that I would never, for example, think about why I walked away from my 1994 Wall Street bonus right in the middle of the year at the worst possible time. That kind of thing just isn’t something you worry about when you’re eighty years old. At the same time, I knew that I might sincerely regret not having participated in this thing called the Internet that I thought was going to be a revolutionizing event. When I thought about it that way… it was incredibly easy to make the decision.”

23. “The whole thing seemed pretty iffy at that stage,” says Kaphan, who some consider an Amazon cofounder. “There wasn’t really anything except for a guy with a barking laugh building desks out of doors in his converted garage.

24. One of their driving goals was to create something superior to the existing online bookstores, including Books.com. “As crazy as it might sound, it did appear that the first challenge was to do something better than these other guys. There was competition already. It wasn’t as if Jeff was coming up with something completely new.”

25. One early challenge was that the book distributors required retailers to order ten books at a time. Amazon didn’t yet have that kind of sales volume, and Bezos later enjoyed telling the story of how he got around it. “We found a loophole,” he said. “Their systems were programmed in such a way that you didn’t have to receive ten books, you only had to order ten books. So we found an obscure book about lichens that they had in their system but was out of stock. We began ordering the one book we wanted and nine copies of the lichen book. They would ship out the book we needed and a note that said, ‘Sorry, but we’re out of the lichen book.

26. The next day, Bezos, MacKenzie, or an employee would drive the boxes to UPS or the post office.

27. Though they could not have known it, investors were looking at the opportunity of a lifetime. This highly driven, articulate young man talked with conviction about the Internet’s potential to deliver a more convenient shopping experience than crowded big-box stores where the staff routinely ignored customers.

28. Bezos was going to do more than establish an online bookstore; now he was set on building one of the first lasting Internet companies.

29. The assumption was that no one would take even a weekend day off.

30. Bezos wanted to reinvent everything about marketing, suggesting, for example, that they conduct annual reviews of advertising agencies to make them constantly compete for Amazon’s business. Breier explained that the advertising industry didn’t work that way. He lasted about a year. Over the first decade at Amazon, marketing VPs were the equivalent of the doomed drummers in the satirical band Spinal Tap; Bezos plowed through them at a rapid clip, looking for someone with the same low regard for the usual way of doing things that Bezos himself had.

31. “You have no physical presence,” the lanky Starbucks founder said as he brewed coffee for his guests. “That is going to hold you back.” Bezos disagreed. He looked right at Schultz and told him, “We are going to take this thing to the moon.”

32. Amazon’s ratio of fixed costs to revenue was considerably more favorable than that of its offline competitors. In other words, Bezos and Covey argued, a dollar that was plugged into Amazon’s infrastructure could lead to exponentially greater returns than a dollar that went into the infrastructure of any other retailer in the world.

33. “Look, you should wake up worried, terrified every morning,” he told his employees. “But don’t be worried about our competitors because they`re never going to send us any money anyway. Let’s be worried about our customers and stay heads-down focused.”

34. In early 1997, Jeff Bezos flew to Boston to give a presentation at the Harvard Business School. He spoke to a class taking a course called Managing the Marketspace, and afterward the graduate students pretended he wasn’t there while they dissected the online retailer’s prospects. At the end of the hour, they reached a consensus: Amazon was unlikely to survive the wave of established retailers moving online. “You seem like a really nice guy, so don’t take this the wrong way, but you really need to sell to Barnes and Noble and get out now." “You may be right,” Amazon’s founder told the students. “But I think you might be underestimating the degree to which established brick-and-mortar business, or any company that might be used to doing things a certain way, will find it hard to be nimble or to focus attention on a new channel. I guess we’ll see.”

35. Wright showed Bezos the blueprints for a new warehouse. The founder’s eyes lit up. “This is beautiful, Jimmy,” Bezos said. Wright asked who he needed to show the plans to and what kind of return on investment he would have to demonstrate. “Don’t worry about that,” Bezos said. “Just get it built.” “Don’t I have to get approval to do this?” Wright asked. “You just did,” Bezos said.

36. Bezos and MacKenzie stopped by Dalzell’s home with a copy of Sam Walton’s autobiography, Sam Walton: Made in America. Bezos had imbibed Walton’s book thoroughly and wove the Walmart founder’s credo about frugality and a “bias for action” into the cultural fabric of Amazon. In the copy he brought to Dalzell, he had underlined one particular passage in which Walton described borrowing the best ideas of his competitors. Bezos’s point was that every company in retail stands on the shoulders of the giants that came before it. The book clearly resonated with Amazon’s founder.

37. On the last page, a section completed a few weeks before his death, Walton wrote: Could a Wal-Mart-type story still occur in this day and age? My answer is of course it could happen again. Somewhere out there right now there’s someone—probably hundreds of thousands of someones—with good enough ideas to go all the way. It will be done again, over and over, providing that someone wants it badly enough to do what it takes to get there. It’s all a matter of attitude and the capacity to constantly study and question the management of the business. Jeff Bezos embodied the qualities Sam Walton wrote about.

38. Jeff didn’t believe in work-life balance. He believed in work-life harmony.

39. Bill Campbell himself revealingly described his role at Amazon this way in an interview with Forbes magazine in 2011: “Jeff Bezos at Amazon—I visited them early on to see if they needed a CEO and I was like, ‘Why would you ever replace him?’ He’s out of his mind, so brilliant about what he does.”

40. Perhaps that is why hyperrational Bezos grew so obsessed with the mild-mannered, bespectacled New York analyst. To Bezos, Suria represented a strain of illogical thinking that had infected the broader market: the notion that the Internet revolution and all of the brash reinvention that accompanied it would just go away.

41. Bezos was obsessed with the customer experience, and anyone who didn’t have the same single-minded focus or who he felt wasn’t demonstrating a capacity for thinking big bore the brunt of his considerable temper.

42. Price came to Amazon in 1999. He blundered early by suggesting in a meeting that Amazon executives who traveled frequently should be permitted to fly business-class. “You would have thought I was trying to stop the Earth from tilting on its axis,” Price says, recalling that moment with horror years later. “Jeff slammed his hand on the table and said, ‘That is not how an owner thinks! That’s the dumbest idea I’ve ever heard.’"

43. In early 2001, Amazon’s position and future prospects remained dubious. Growth appeared to be slowing.

44. Bezos met Jim Sinegal, the founder of Costco. Sinegal was a casual, plain-speaking native of Pittsburgh, a Wilford Brimley look-alike with a bushy white mustache and an amiable countenance that concealed the steely determination of an entrepreneur. Well into retirement age, he showed no interest in slowing down. The two had plenty in common. For years Sinegal, like Bezos, had battled Wall Street analysts who wanted him to raise Costco’s prices on clothing, appliances, and packaged foods. Like Bezos, Sinegal had rejected multiple acquisition offers over the years, including one from Sam Walton, and he liked to say he didn’t have an exit strategy—he was building a company for the long term.

Bezos listened carefully and once again drew key lessons from a more experienced retail veteran. Sinegal explained the Costco model to Bezos: it was all about customer loyalty. There are some four thousand products in the average Costco warehouse, including limited-quantity seasonal or trendy products called treasure-hunt items that are spread out around the building. Though the selection of products in individual categories is limited, there are copious quantities of everything there—and it is all dirt cheap. Costco buys in bulk and marks up everything at a standard, across-the-board 14 percent, even when it could charge more. It doesn’t advertise at all, and earns most of its gross profit from the annual membership fees. “The membership fee is a onetime pain, but it’s reinforced every time customers walk in and see forty-seven-inch televisions that are two hundred dollars less than anyplace else,” Sinegal said. “It reinforces the value of the concept. Customers know they will find really cheap stuff at Costco.”

“My approach has always been that value trumps everything,” Sinegal continued. “The reason people are prepared to come to our strange places to shop is that we have value. We deliver on that value.

45. The Monday after the meeting with Sinegal, Bezos opened an S Team meeting by saying he was determined to make a change. The company’s pricing strategy, he said, according to several executives who were there, was incoherent. Amazon preached low prices but in some cases its prices were higher than competitors’. Like Walmart and Costco, Bezos said, Amazon should have “everyday low prices.” The company should look at other large retailers and match their lowest prices, all the time. If Amazon could stay competitive on price, it could win the day on unlimited selection and on the convenience afforded to customers who didn’t have to get in the car to go to a store and wait in line.

46. If you’re not good, Jeff will chew you up and spit you out. And if you’re good, he will jump on your back and ride you into the ground.

47. "I understand what you’re saying, but you are completely wrong,” he said. “Communication is a sign of dysfunction. It means people aren’t working together in a close, organic way. We should be trying to figure out a way for teams to communicate less with each other, not more.” Bezos’s counterintuitive point was that coordination among employees wasted time, and that the people closest to problems were usually in the best position to solve them.

48. “Jeff does a couple of things better than anyone I’ve ever worked for,” Dalzell says. “He embraces the truth. A lot of people talk about the truth, but they don’t engage their decision-making around the best truth at the time. “The second thing is that he is not tethered by conventional thinking. What is amazing to me is that he is bound only by the laws of physics. He can’t change those. Everything else he views as open to discussion.”

49. Think Big Thinking small is a self-fulfilling prophecy. Leaders create and communicate a bold direction that inspires results. They think differently and look around corners for ways to serve customers.

Learn from history's greatest entrepreneurs by listening to Founders. Every week I read a biography of an entrepreneur and find ideas you can use in your work.

2. Relentless and ruthless. Those words show up repeatedly in the following pages. They are extreme but familiar values at most successful companies. Getting the lethal combination precisely right has been Bezos’s prodigious talent and perhaps Amazon’s greatest asset.

3. There is so much stuff that has yet to be invented. There’s so much new that’s going to happen.

4. Amazon’s internal customs are deeply idiosyncratic.

5. “If you want to get to the truth about what makes us different, it’s this,” Bezos says, “We are genuinely customer-centric, we are genuinely long-term oriented and we genuinely like to invent. Most companies are not those things. They are focused on the competitor, rather than the customer. They want to work on things that will pay dividends in two or three years, and if they don’t work in two or three years they will move on to something else. And they prefer to be close-followers rather than inventors, because it’s safer. So if you want to capture the truth about Amazon, that is why we are different. Very few companies have all of those three elements.”

6. I brought him very bad news about our business, and for some reason, he got excited.

7. The goal of this book is to tell the story behind one of the greatest entrepreneurial successes since Sam Walton flew his two-seat turboprop across the American South to scope out prospective Walmart store sites. It’s the tale of how one gifted child grew into an extraordinarily driven and versatile CEO and how he, his family, and his colleagues bet heavily on a revolutionary network called the Internet, and on the grandiose vision of a single store that sells everything.

8. Amazon.com was an idea floating through the New York City offices of one of the most unusual firms on Wall Street: D. E. Shaw & Co. A quantitative hedge fund, DESCO, as its employees affectionately called it, was started in 1988 by David E. Shaw, a former Columbia University computer science professor. Along with the founders of other groundbreaking quant houses of that era, like Renaissance Technologies and Tudor Investment Corporation, Shaw pioneered the use of computers and sophisticated mathematical formulas to exploit anomalous patterns in global financial markets.

9. The broader financial community knew very little about D. E. Shaw, and its polymath founder wanted to keep it that way.

10. Shaw felt strongly that if DESCO was going to be a firm that pioneered new approaches to investing, the only way to maintain its lead was to keep its insights secret and avoid teaching competitors how to think about these new computer-guided frontiers.

11. Bezos was in his midtwenties at the time, five foot eight inches tall, already balding and with the pasty, rumpled appearance of a committed workaholic. He had spent five years on Wall Street and impressed seemingly everyone he encountered with his keen intellect and boundless determination.

12. Minor remembers that Bezos had closely studied several wealthy businessmen and that he particularly admired a man named Frank Meeks, a Virginia entrepreneur who had made a fortune owning Domino’s Pizza franchises.

13. Bezos also revered pioneering computer scientist Alan Kay and often quoted his observation that “point of view is worth 80 IQ points”—a reminder that looking at things in new ways can enhance one’s understanding.

14. He went to school on everybody. I don’t think there was anybody Jeff knew that he didn’t walk away from with whatever lessons he could.

15. Bezos would later say he found a kind of workplace soul mate in David Shaw—“one of the few people I know who has a fully developed left brain and a fully developed right brain.”

16. At DESCO, Bezos displayed many of the idiosyncratic qualities his employees would later observe at Amazon. He was disciplined and precise, constantly recording ideas in a notebook he carried with him, as if they might float out of his mind if he didn’t jot them down. He quickly abandoned old notions and embraced new ones when better options presented themselves.

17. He was “the most introspective guy I ever met. He was very methodical about everything in his life.”

18. So in 1994, when the opportunity of the Internet began to reveal itself to the few people watching closely, Shaw felt that his company was uniquely positioned to exploit it. And the person he anointed to spearhead the effort was Jeff Bezos.

19. Shaw and Bezos discussed another idea as well. They called it “the everything store.”

20. Bezos interpolated from this that Web activity overall had gone up that year by a factor of roughly 2,300—a 230,000 percent increase. “Things just don’t grow that fast,” Bezos later said. “It’s highly unusual, and that started me thinking, What kind of business plan might make sense in the context of that growth?”

21. What happened next became one of the founding legends of the Internet. That spring, Bezos spoke to David Shaw and told him he planned to leave the company to create an online bookstore. Shaw suggested they take a walk. They wandered in Central Park for two hours, discussing the venture and the entrepreneurial drive. Shaw said he understood Bezos’s impulse and sympathized with it—he had done the same thing when he’d left Morgan Stanley. He also noted that D. E. Shaw was growing quickly and that Bezos already had a great job. He told Bezos that the firm might end up competing with his new venture. The two agreed that Bezos would spend a few days thinking about it.

22. Bezos would later describe his thinking process in unusually geeky terms. He says he came up with what he called a “regret-minimization framework” to decide the next step to take at this juncture of his career. “When you are in the thick of things, you can get confused by small stuff,” Bezos said a few years later. “I knew when I was eighty that I would never, for example, think about why I walked away from my 1994 Wall Street bonus right in the middle of the year at the worst possible time. That kind of thing just isn’t something you worry about when you’re eighty years old. At the same time, I knew that I might sincerely regret not having participated in this thing called the Internet that I thought was going to be a revolutionizing event. When I thought about it that way… it was incredibly easy to make the decision.”

23. “The whole thing seemed pretty iffy at that stage,” says Kaphan, who some consider an Amazon cofounder. “There wasn’t really anything except for a guy with a barking laugh building desks out of doors in his converted garage.

24. One of their driving goals was to create something superior to the existing online bookstores, including Books.com. “As crazy as it might sound, it did appear that the first challenge was to do something better than these other guys. There was competition already. It wasn’t as if Jeff was coming up with something completely new.”

25. One early challenge was that the book distributors required retailers to order ten books at a time. Amazon didn’t yet have that kind of sales volume, and Bezos later enjoyed telling the story of how he got around it. “We found a loophole,” he said. “Their systems were programmed in such a way that you didn’t have to receive ten books, you only had to order ten books. So we found an obscure book about lichens that they had in their system but was out of stock. We began ordering the one book we wanted and nine copies of the lichen book. They would ship out the book we needed and a note that said, ‘Sorry, but we’re out of the lichen book.

26. The next day, Bezos, MacKenzie, or an employee would drive the boxes to UPS or the post office.

27. Though they could not have known it, investors were looking at the opportunity of a lifetime. This highly driven, articulate young man talked with conviction about the Internet’s potential to deliver a more convenient shopping experience than crowded big-box stores where the staff routinely ignored customers.

28. Bezos was going to do more than establish an online bookstore; now he was set on building one of the first lasting Internet companies.

29. The assumption was that no one would take even a weekend day off.

30. Bezos wanted to reinvent everything about marketing, suggesting, for example, that they conduct annual reviews of advertising agencies to make them constantly compete for Amazon’s business. Breier explained that the advertising industry didn’t work that way. He lasted about a year. Over the first decade at Amazon, marketing VPs were the equivalent of the doomed drummers in the satirical band Spinal Tap; Bezos plowed through them at a rapid clip, looking for someone with the same low regard for the usual way of doing things that Bezos himself had.

31. “You have no physical presence,” the lanky Starbucks founder said as he brewed coffee for his guests. “That is going to hold you back.” Bezos disagreed. He looked right at Schultz and told him, “We are going to take this thing to the moon.”

32. Amazon’s ratio of fixed costs to revenue was considerably more favorable than that of its offline competitors. In other words, Bezos and Covey argued, a dollar that was plugged into Amazon’s infrastructure could lead to exponentially greater returns than a dollar that went into the infrastructure of any other retailer in the world.

33. “Look, you should wake up worried, terrified every morning,” he told his employees. “But don’t be worried about our competitors because they`re never going to send us any money anyway. Let’s be worried about our customers and stay heads-down focused.”

34. In early 1997, Jeff Bezos flew to Boston to give a presentation at the Harvard Business School. He spoke to a class taking a course called Managing the Marketspace, and afterward the graduate students pretended he wasn’t there while they dissected the online retailer’s prospects. At the end of the hour, they reached a consensus: Amazon was unlikely to survive the wave of established retailers moving online. “You seem like a really nice guy, so don’t take this the wrong way, but you really need to sell to Barnes and Noble and get out now." “You may be right,” Amazon’s founder told the students. “But I think you might be underestimating the degree to which established brick-and-mortar business, or any company that might be used to doing things a certain way, will find it hard to be nimble or to focus attention on a new channel. I guess we’ll see.”

35. Wright showed Bezos the blueprints for a new warehouse. The founder’s eyes lit up. “This is beautiful, Jimmy,” Bezos said. Wright asked who he needed to show the plans to and what kind of return on investment he would have to demonstrate. “Don’t worry about that,” Bezos said. “Just get it built.” “Don’t I have to get approval to do this?” Wright asked. “You just did,” Bezos said.

36. Bezos and MacKenzie stopped by Dalzell’s home with a copy of Sam Walton’s autobiography, Sam Walton: Made in America. Bezos had imbibed Walton’s book thoroughly and wove the Walmart founder’s credo about frugality and a “bias for action” into the cultural fabric of Amazon. In the copy he brought to Dalzell, he had underlined one particular passage in which Walton described borrowing the best ideas of his competitors. Bezos’s point was that every company in retail stands on the shoulders of the giants that came before it. The book clearly resonated with Amazon’s founder.

37. On the last page, a section completed a few weeks before his death, Walton wrote: Could a Wal-Mart-type story still occur in this day and age? My answer is of course it could happen again. Somewhere out there right now there’s someone—probably hundreds of thousands of someones—with good enough ideas to go all the way. It will be done again, over and over, providing that someone wants it badly enough to do what it takes to get there. It’s all a matter of attitude and the capacity to constantly study and question the management of the business. Jeff Bezos embodied the qualities Sam Walton wrote about.

38. Jeff didn’t believe in work-life balance. He believed in work-life harmony.

39. Bill Campbell himself revealingly described his role at Amazon this way in an interview with Forbes magazine in 2011: “Jeff Bezos at Amazon—I visited them early on to see if they needed a CEO and I was like, ‘Why would you ever replace him?’ He’s out of his mind, so brilliant about what he does.”

40. Perhaps that is why hyperrational Bezos grew so obsessed with the mild-mannered, bespectacled New York analyst. To Bezos, Suria represented a strain of illogical thinking that had infected the broader market: the notion that the Internet revolution and all of the brash reinvention that accompanied it would just go away.

41. Bezos was obsessed with the customer experience, and anyone who didn’t have the same single-minded focus or who he felt wasn’t demonstrating a capacity for thinking big bore the brunt of his considerable temper.

42. Price came to Amazon in 1999. He blundered early by suggesting in a meeting that Amazon executives who traveled frequently should be permitted to fly business-class. “You would have thought I was trying to stop the Earth from tilting on its axis,” Price says, recalling that moment with horror years later. “Jeff slammed his hand on the table and said, ‘That is not how an owner thinks! That’s the dumbest idea I’ve ever heard.’"

43. In early 2001, Amazon’s position and future prospects remained dubious. Growth appeared to be slowing.

44. Bezos met Jim Sinegal, the founder of Costco. Sinegal was a casual, plain-speaking native of Pittsburgh, a Wilford Brimley look-alike with a bushy white mustache and an amiable countenance that concealed the steely determination of an entrepreneur. Well into retirement age, he showed no interest in slowing down. The two had plenty in common. For years Sinegal, like Bezos, had battled Wall Street analysts who wanted him to raise Costco’s prices on clothing, appliances, and packaged foods. Like Bezos, Sinegal had rejected multiple acquisition offers over the years, including one from Sam Walton, and he liked to say he didn’t have an exit strategy—he was building a company for the long term.

Bezos listened carefully and once again drew key lessons from a more experienced retail veteran. Sinegal explained the Costco model to Bezos: it was all about customer loyalty. There are some four thousand products in the average Costco warehouse, including limited-quantity seasonal or trendy products called treasure-hunt items that are spread out around the building. Though the selection of products in individual categories is limited, there are copious quantities of everything there—and it is all dirt cheap. Costco buys in bulk and marks up everything at a standard, across-the-board 14 percent, even when it could charge more. It doesn’t advertise at all, and earns most of its gross profit from the annual membership fees. “The membership fee is a onetime pain, but it’s reinforced every time customers walk in and see forty-seven-inch televisions that are two hundred dollars less than anyplace else,” Sinegal said. “It reinforces the value of the concept. Customers know they will find really cheap stuff at Costco.”

“My approach has always been that value trumps everything,” Sinegal continued. “The reason people are prepared to come to our strange places to shop is that we have value. We deliver on that value.

45. The Monday after the meeting with Sinegal, Bezos opened an S Team meeting by saying he was determined to make a change. The company’s pricing strategy, he said, according to several executives who were there, was incoherent. Amazon preached low prices but in some cases its prices were higher than competitors’. Like Walmart and Costco, Bezos said, Amazon should have “everyday low prices.” The company should look at other large retailers and match their lowest prices, all the time. If Amazon could stay competitive on price, it could win the day on unlimited selection and on the convenience afforded to customers who didn’t have to get in the car to go to a store and wait in line.

46. If you’re not good, Jeff will chew you up and spit you out. And if you’re good, he will jump on your back and ride you into the ground.

47. "I understand what you’re saying, but you are completely wrong,” he said. “Communication is a sign of dysfunction. It means people aren’t working together in a close, organic way. We should be trying to figure out a way for teams to communicate less with each other, not more.” Bezos’s counterintuitive point was that coordination among employees wasted time, and that the people closest to problems were usually in the best position to solve them.

48. “Jeff does a couple of things better than anyone I’ve ever worked for,” Dalzell says. “He embraces the truth. A lot of people talk about the truth, but they don’t engage their decision-making around the best truth at the time. “The second thing is that he is not tethered by conventional thinking. What is amazing to me is that he is bound only by the laws of physics. He can’t change those. Everything else he views as open to discussion.”

49. Think Big Thinking small is a self-fulfilling prophecy. Leaders create and communicate a bold direction that inspires results. They think differently and look around corners for ways to serve customers.

Learn from history's greatest entrepreneurs by listening to Founders. Every week I read a biography of an entrepreneur and find ideas you can use in your work.