My highlights from the book:

1. It dawned on me that the hordes of financial novices might be ripe for a history that would chronicle how the old Wall Street evolved into the new. A straight history would be a tedious task for readers and do small justice to the turbulent pageant of heroes and scoundrels I was unearthing.

2. So I posed the question: was there a single family or firm whose saga could serve as a prism through which to view the panoramic saga of Anglo-American finance?

3. Only one firm, one family, one name rather gloriously spanned the entire century and a half that I wanted to cover: J.P. Morgan.

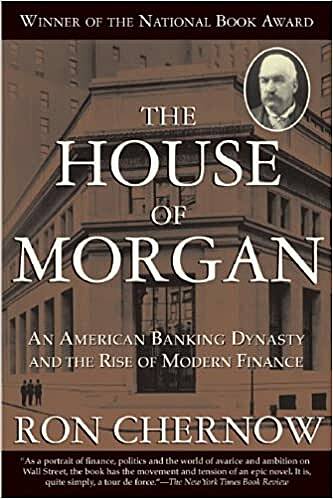

4. This book is about the rise, fall, and resurrection of an American banking empire—the House of Morgan.

5. Nobody was ever neutral about the Morgans.

6. They practiced a brand of baking that has little resemblance to standard retail banking. These banks have no tellers, issue no consumer loans, and grant no mortgages. Rather, they serve an ancient European tradition of wholesale banking, serving governments, large corporations, and rich individuals.

7. They avoid branches, seldom hang out signposts, and wouldn’t advertise.

8. Contrary to the usual law of perspective, the Morgans seem to grow larger as they recede in time.

9. George Peabody would found the House of Morgan.

10. He carried the scars of early poverty. Like many who have overcome early hardship by brute force, he was proud but insecure, always at war with the world and counting his injuries.

11. He remained haunted by his past. “I have never forgotten and never can forget the great privations of my early years,” he later said. He hoarded his money and worked incessantly.

12. During one twelve-year period, he never took off two consecutive days and spent an average of ten hours per day at work.

13. Peabody amassed a $20 million fortune in the 1850s as he financed everything from the silk trade with China to iron rail exports to America.

14. My capital is ample but I have passed too many money panics unscathed, not to have seen how often large Capitals are swept away, and that even with my own I must use caution.

15. His annual savings were staggering: he spent only $3,000 of a total annual income of $300,000.

16. Junius Morgan began to lecture his son on the need for conservative business practice, the panic of 1857 would be the text of many sermons. “You are commencing upon your business career at an eventful time. Let what you now witness make an impression not to be eradicated. Slow and sure should be the motto of every young man.”

17. The Morgans always believed in absolute monarchy. While Junius Morgan lived, he ruled the family and the business. Until Junius died his massive shadow dominated his son’s life.

18. Junius employed iron discipline.

19. Early on, Pierpont figured in his father’s business plans. Junius knew the Rothschild operated largely as a family enterprise, grooming sons to inherit their respective businesses.

20. When Pierpont was twenty-one, Junius told him he was “the only one [the family] could look to for counsel and direction should I be taken from them. I wish to impress upon you the necessity of preparation for such responsibilities.”

21. The father-son team of Junius and Pierpont Morgan came on the world banking scene at a time of phenomenal expansion of banking power. It coincided with the rise of railroads and heavy industry, new businesses requiring capital far beyond the resources of even the wealthiest individuals or families.

22. No less than to industry, bankers dictated terms to sovereign states and countries.

23. Junius was extremely selective about the business he did and had learned the need for caution. “Never under any circumstances do an action which would be called in question if known to the world.”

24. The railroads would unlock the resources in the American wilderness. Perhaps no business has ever blossomed so spectacularly. More than just isolated businesses, railroads were the scaffolding on which new worlds would be built.

25. Not for the last time, Pierpont contemplated retirement. As if unable to stop his own ambition, he would assume tremendous responsibility, then feel oppressed. He never seemed to take great pleasure in his accomplishments, and craved a restful but elusive peace.

26. At work, Pierpont could never relax and developed a powerful urge to escape. He would vacation three months each year.

27. Pierpont managed a handy profit in the panic year of 1873. He made over $1 million, boasting to Junius: “I don’t believe there is another concern in the country that can begin to show such a result.”

28. Pierpont decided to limit his future dealings to elite companies. He became the sort of tycoon who hated risk and wanted only sure things. “I have come to the conclusion that neither my firm nor myself will have anything to do with the negotiation of securities of any undertaking not entirely completed; and whose status, by experience, would not prove it entitled to a credit in every respect unassailable.”

29. This encapsulated future Morgan strategy—dealing only with the strongest companies and shying away from speculative ventures.

30. The story of Pierpont Morgan is that of a young moralist turned despot, one who believed implicitly in the correctness of his views.

31. He believed that he knew how the economy should be ordered and how people should behave.

32. He had trouble delegating authority and a low regard for the intelligence of other people. “The longer I live the more apparent becomes the absence of brains.”

33. Perhaps never in financial history has anybody else amassed so much power so reluctantly. J. Pierpont Morgan was more exhausted than exhilarated with success. He didn’t enjoy responsibility and never learned to cope with it.

34. Under his sometimes stern facade, Junius clearly adored Pierpont; the obsessive grooming was a tacit acknowledgment of his son’s gifts.

35. Yet again Pierpont contemplated giving up business: I am pressed beyond measure. I have had no leisure whatever. If it were simply my own affairs that were concerned, I would very soon settle the question, and give it up; but with the large interests of others on my shoulders, it cannot be done. I often think it would be very desirable if I could have more time for outside matters.

36. Pierpont was, by nature, a laconic man. He had no gift for sustained analysis; his genius was in the brief, sudden brainstorm.

37. Morgan has one chief mental asset—a tremendous five minutes’ concentration of thought.

38. Among robber barons, he was unique in suffering an excess of morality. He believed that he could master the problems of his era at a time when others were confused by the sheer dynamism and speed of economic change.

39. There are many stories of Pierpont’s brusque impatience and his economy of self-expression.

40. He had a short attention span.

41. He had long bewailed his inability to delegate authority: “It is my nature and I cannot help it.”

42. Pierpont was extremely attentive to details and took pride in the knowledge that he could perform any job in the bank: “I can sit down at any clear’s desk, take up his work where he left it and go on with it. I don’t like being at any man’s mercy.”

43. He never entirely renounced the founder’s itch to know the most minute details of the business.

44. Oppressed by debt and overbuilding, more than a third of the country’s railroads fell into receivership. Pierpont would reorganize bankrupt roads and transfer control to himself. Virtually every bankrupt road east of the Mississippi eventually passed through such reorganization, or Morganization, as it was called.

45. He has the driving power of a locomotive. Something brutish and uncontrollable, but also something of superhuman strength.

46. He saw competition as a destructive, inefficient force and favored large-scale combination as the cure. Once, when the manager of the Moet and Chandon wine company complained about industry problems, Pierpont suggested he buy up the entire champagne country.

47. Andrew Carnegie celebrated too quickly. He later admitted to Morgan that he had sold out too cheap, by $100 million. Morgan replied, “Very likely, Andrew.”

48. McKinley’s assassination would be a turning point in Pierpont Morgan’s life, for it installed in the presidency Theodore Roosevelt, a man whose view of big business was far more ambivalent than his predecessor’s.

49. Pierpont once told an associate, “A man always has two reasons for the things he does—a good one and the real one.”

50. He was the embodiment of power and purpose.

51. This was Pierpont in a nutshell: he represented the bondholders and expressed their wrath against irresponsible management.

Learn more ideas from history's greatest entrepreneurs by listening to Founders podcast. Read more highlights.